Magnetar Near Supermassive Black Hole Delivers Surprises

In 2013, astronomers announced they had discovered a magnetar exceptionally close to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way using a suite of space-borne telescopes including NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Magnetars are dense, collapsed stars (called "neutron stars") that possess enormously powerful magnetic fields. At a distance that could be as small as 0.3 light years (or about 2 trillion miles) from the 4-million-solar mass black hole in the center of our Milky Way galaxy, the magnetar is by far the closest neutron star to a supermassive black hole ever discovered and is likely in its gravitational grip.

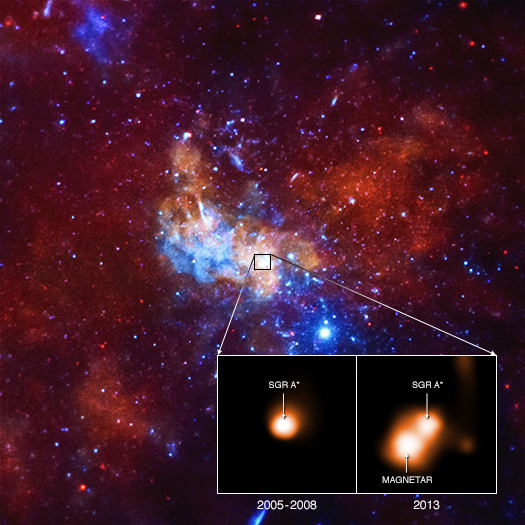

Since its discovery two years ago when it gave off a burst of X-rays, astronomers have been actively monitoring the magnetar, dubbed SGR 1745-2900, with Chandra and the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton. The main image of the graphic shows the region around the Milky Way's black hole in X-rays from Chandra (red, green, and blue are the low, medium, and high-energy X-rays respectively). The inset contains Chandra's close-up look at the area right around the black hole, showing a combined image obtained between 2005 and 2008 (left) when the magnetar was not detected, during a quiescent period, and an observation in 2013 (right) when it was caught as a bright point source during the X-ray outburst that led to its discovery.

A new study uses long-term monitoring observations to reveal that the amount of X-rays from SGR 1745-2900 is dropping more slowly than other previously observed magnetars, and its surface is hotter than expected.

The team first considered whether "starquakes" are able to explain this unusual behavior. When neutron stars, including magnetars, form, they can develop a tough crust on the outside of the condensed star. Occasionally, this outer crust will crack, similar to how the Earth's surface can fracture during an earthquake. Although starquakes can explain the change in brightness and cooling seen in many magnetars, the authors found that this mechanism by itself was unable to explain the slow drop in X-ray brightness and the hot crustal temperature. Fading in X-ray brightness and surface cooling occur too quickly in the starquake model.

More information at http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2015/sgr1745/index.html

-Megan Watzke, CXC

Category:

- Log in to post comments