The Great and the Small: Is Quantum Foam Losing its Fizz?

Eric Perlman

We are very pleased to welcome Eric Perlman as a guest blogger today. He led the study setting limits on the foaminess of space-time that is the subject of our latest press release. Eric is a professor at the Florida Institute of Technology. After completing his PhD in 1994 at the University of Colorado, he held postdoctoral fellowships at the Goddard Space Flight Center and Space Telescope Science Institute. He also held research positions at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He has lived in Florida for 8 years and enjoys his family, singing, and playing chess and other board games.

Astronomy has been a tool of discovery since the dawn of civilization. For thousands of years, humans used the stars to navigate and find their place in the universe. Astronomy made possible the travels of the ancient Polynesians across the Pacific Ocean as well as measurements of the Earth’s size and shape by the ancient Greeks. Today, astronomers search for hints about what the universe was like when the universe was much younger. So imagine, for a second, what life would be like – and how much less we would know about ourselves and the universe – if the microscopic nature of space-time made some of these measurements impossible.

This is the puzzle posed by our observations of very distant objects in X-rays and gamma-rays, and for me as an astronomer, it is a mind-blowing concept I never thought I would have to deal with. I have always been interested in quasars, both because of the extreme physics that can occur near their central supermassive black holes or in their energetic outflows called jets, as well as because of the unique insights that can be gained because of the fact that they are the brightest and most luminous things that we can see from the earliest stages of the universe’s evolution.

I got interested in the structure of space-time almost by serendipity. Fifteen years ago, I wrote a paper on Hubble Space Telescope observations of a quasar, PKS 1413+135, where the galaxy’s nucleus was so bright that one could easily see Airy rings – artifacts that are always observed when one takes high-quality images of an unresolved source. Two years later, Richard Lieu and Lloyd Hillman of the University of Alabama in Huntsville, wrote a paper claiming that the mere fact that those images existed ruled out models of quantum gravity. This was then disputed by two of my co-authors, Y. Jack Ng and Wayne Christiansen of the University of North Carolina. In 2005, I was asked to review one of their papers by the editor of Physical Review Letters. I became so fascinated with the topic that after their paper was published, I contacted them with an idea of my own. Jack, Wayne and I, along with other collaborators, have worked together on this subject since that time.

What is it about space and time that might determine whether we could even take images of a distant object? The answer lies in the nature of space-time itself and how light travels. Light travels along a path called a null geodetic. This is the shortest distance between two points. In the absence of gravity, a null geodetic is represented by a straight line. But if a mass is present, the null geodetic represents the shortest-distance path through the curved space-time. Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity (GR) describes how mass curves space-time, an effect we can see in such varied ways as gravitational lensing by distant galaxies, the precession of Mercury’s orbit, and the relativistic frame-dragging that is observed in the variability of X-ray binaries.

Illustration of Space-time foam

In GR, there are four dimensions, three of space and one of time. One of the greatest puzzles of modern physics is why gravity (and GR) cannot be unified with quantum mechanics (which has been immensely effective in describing the structure of atoms), as the electromagnetic and other forces have been. Quantum gravity models predict that space-time has a foamy structure (see artist’s conception, above), with tiny bubbles that are constantly fluctuating. These bubbles – which are quadrillions of times

smaller than atomic nuclei and last for infinitesimal fractions of a second (far shorter than the femtosecond bursts from the fastest lasers) – must be described by additional dimensions. Because these bubbles are so small and last for such a short time, they can never be observed directly. But they would affect light in an interesting way: because of the fluctuating nature of space-time, each photon would take a slightly different path to us, and hence the distance that it travels would be different. We could still never observe a single deflection imposed by quantum foam. But if you observe a very distant object, each photon will go through many of these fluctuations, and the fluctuations could add up – although exactly how depends on the model of quantum gravity. These fluctuations would then cause the wavefronts we observe to be distorted ever so slightly. If the accumulated distortions become comparable to the wavelength of light we’re observing, it would be impossible to form an image, no matter how good your telescope is – just like trying to distinguish sounds emitted by many out-of-phase loudspeakers, they would become pure noise.

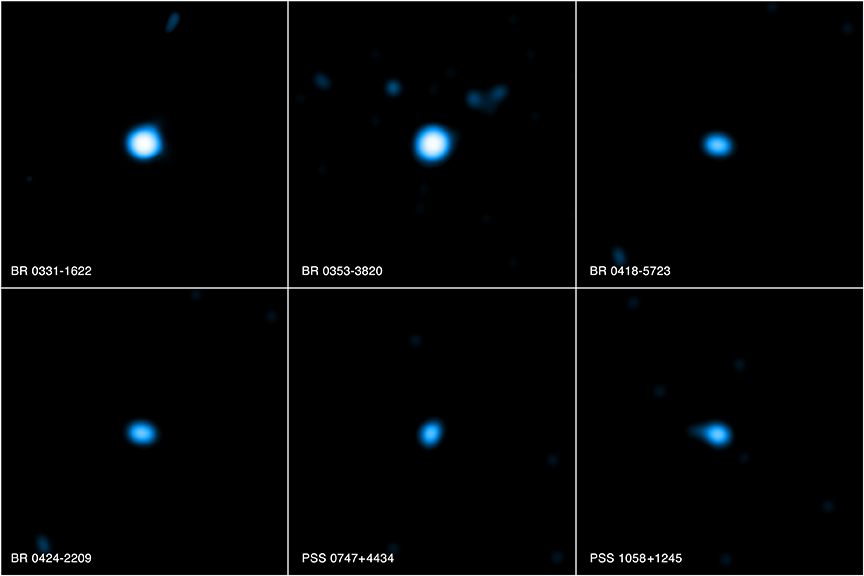

This was the effect that we wanted to search for, which previous papers had not described properly. We modeled these effects, and then used observations of distant quasars by the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System, known as VERITAS, to look at archival images of the most distant quasars. We wanted to look in the X-rays and gamma-rays because of their short wavelength – allowing us to possibly observe the smallest possible distortions in the wavefronts by quantum gravity. But even the most distant quasars (see examples, below) appear to form sharp X-ray and gamma-ray images. Two models of quantum foam had predicted that these images would disappear at short wavelengths. Chandra’s X-ray images rules out one model, according to which photons diffuse randomly through space-time foam in a manner similar to light diffusing through fog. And gamma-ray images with Fermi and VERITAS, demonstrate that a so-called holographic model with less diffusion does not work.

So where does this leave us? Space-time appears to be smooth, at least on scales of 10-16 cm, a thousand times smaller than an atomic nucleus, and space-time must be much less foamy than most models predict. And, right now the only model that seems to hold up, predicts that space-time fluctuations should be anti-correlated with one another and so would not add up over long distances. While philosophically, it may be reassuring to not have to think of space-time as having a foamy nature that can affect one’s ability to see distant objects, on another level it makes the small scale structure of the universe even more puzzling.

Category:

- Log in to post comments