April 19, 2005

CXC RELEASE 05-05

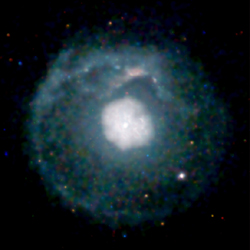

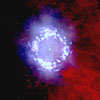

Two scientists have discovered a distinctive shell of hot gas around the site of a distant supernova explosion by combining 150 hours of archived data collected by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. This discovery is a significant step forward in solving a decades-old puzzle as to why some stellar explosions display shells and others do not.

"The likely answer is that the explosion of every massive star sends a sonic boom rumbling through interstellar space," said Samar Safi-Harb of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, who is a coauthor with Heather Matheson on a paper describing the research that appears in the journal Advances in Space Research. "It's just that, some of the shells are harder to find than others because of the environment where the explosion occurs."

The shell marks a sonic boom, or shock wave, generated by the supernova. Gas is heated to millions of degrees by the shock wave and produces X-rays, but little visible light. By examining the properties of the shell with an X-ray telescope, astronomers can work back to deduce the age (a few thousand years), and energy of the explosion, as well as information about the state of the star a million years before it exploded.

It is likely that the star that produced the supernova remnant and shell was about 10 times as massive as the Sun. The absence of a detectable shell around this and similar supernova remnants had led astronomers to speculate that another, weaker type of explosion had occurred there. Now this hypothesis seems unlikely.

Although many supernovas leave behind bright shells, others do not. This supernova remnant, identified as G21.5-0.9 by radio astronomers 30 years ago, was considered to be one that had no shell. A diffuse cloud of X-rays around the source was detected about 5 years ago by another group of astronomers and independently by Safi-Harb and colleagues using Chandra, but it took the careful combining of large amounts of data from the Chandra archives to prove that the shell exists.

The faintness of supernova shells is likely attributed to a lack of material around the star before it explodes. Rapid mass loss from the star for a few hundred thousand years could have cleared out the region before the explosion.

The scientist also uncovered evidence that the supernova left behind a rapidly rotating neutron star, or pulsar. Faint X-ray filaments, or wisps, close to the center of the supernova remnant might be from winds and jets of high energy electrons generated by the pulsar.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Northrop Grumman of Redondo Beach, Calif., was the prime development contractor for the observatory. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory controls science and flight operations from the Chandra X-ray Center in Cambridge, Mass.

Additional information and images are available at:

MEDIA CONTACTS

Steve Roy

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL

Phone: 256-544-6535

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, CfA, Cambridge, MA

Phone: 617-496-7998