For Release: August 14, 2024

NASA/CXC

Astronomers have correctly forecast when a giant black hole finished its last meal — and predict when its next snack will occur.

Using new data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory as well as ESA’s (European Space Agency’s) XMM-Newton, a team of researchers have made important headway in understanding how — and when — this supermassive black hole consumes material.

This result is based on studies of a supermassive black hole — with about 50 million times more mass than the Sun — in the center of a galaxy located about 860 million light-years from Earth.

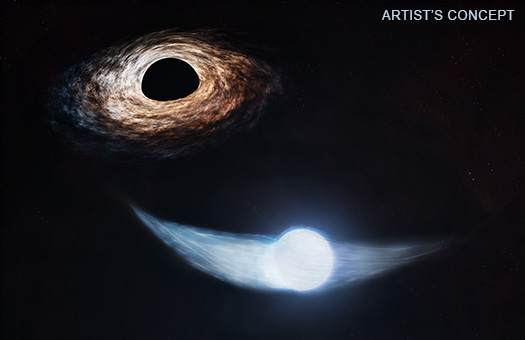

In 2018, the optical All Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae noticed this system had become much brighter. After observing it with NASA’s NICER (Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer) and Chandra, and XMM-Newton, researchers determined that the surge in brightness came from a “tidal disruption event,” which signals that a star was completely torn apart and partially ingested after flying too close to a black hole. They called the tidal disruption event AT2018fyk.

When material from the destroyed star approached close to the black hole, it got hotter and produced X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) light. These signals then faded, suggesting that nothing was left of the star for the black hole to digest.

However, about two years later, the X-ray and UV light from the galaxy got much brighter again. According to astronomers, the most plausible explanation was that the star likely survived the initial gravitational grab by the black hole and then entered a highly elliptical orbit with the black hole. During its second close approach to the black hole, more material was pulled off, producing more X-ray and UV light.

These results were published in a 2023 paper in the Astrophysical Journal Letters led by Thomas Wevers from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

“Initially we thought this was a garden-variety case of a black hole totally ripping a star apart,” said Wevers. “But instead, the star appears to be living to die another day.”

Based on what they had learned about the star and its orbit, Wevers and his team predicted that the black hole’s second meal would end in August 2023, and applied for Chandra observing time to check.

“The telltale sign of this stellar snack ending would be a sudden drop in the X-rays and that’s exactly what we see in our Chandra observations on Aug. 14, 2023,” said Dheeraj Pasham of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the leader of a new paper on these results. “Our data show that in August last year, the black hole was essentially wiping its mouth and pushing back from the table.”

New data obtained by Chandra and Swift after the 2023 paper was completed gives the researchers an even better estimate of how long it takes the star to complete an orbit, and future mealtimes for the black hole. They determine that the star makes its closest approach to the black hole about once every three and a half years.

“We think that a third meal by the black hole, if anything is left of the star, will begin between May and August of 2025 and last for almost two years,” said Eric Coughlin, a co-author of the new paper, from Syracuse University in New York. “This will probably be more of a snack than a full meal because the second meal was smaller than the first, and the star is being whittled away.”

The authors think that the doomed star originally had another star as a companion as it approached the black hole. When the stellar pair got too close to the black hole, however, the gravity from the black hole pulled the two stars apart. One entered the orbit with the black hole, and the other was tossed into space at high speed.

“The doomed star was forced to make a drastic change in companions — from another star to a giant black hole,” said co-author Muryel Guolo of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “Its stellar partner escaped, but it did not.”

The team plans to keep following AT2018fyk for as long as they can to study the behavior of such an exotic system.

A paper describing these results appears in the latest issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters and is available online at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18124.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Media Contact:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Jonathan Deal

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama

256-544-0034

jonathan.e.deal@nasa.gov