Quasars look like any normal star through an optical telescope. It wasn’t until the 1950’s, when radio astronomy was first developed, that astronomers realized these extragalactic objects are emitting massive amounts of radio energy. This important discovery was named a quasar, short for “Quasi-stellar radio source”. By waiting for known radio sources to pass behind the moon, optical and radio data could be combined to give astronomers the precise location of quasars in the sky.

Quasars are among the most distant, energetic objects ever observed. Even though individual quasars are brighter than hundreds of galaxies put together, many are smaller than the size of our own solar system.

Radio astronomers use a system of numbers to name objects in the sky. 3C273 was named in the 3rd Cambridge catalog as the 273rd radio source identified. 3C273, along with 3C48, were the first quasars to be identified. These objects had bizarre spectra unlike any ever studied before. In 1963 astronomers Maarten Schmidt (3C273) and Jesse Greenstein and Thomas Matthews (3C48) noticed that the spectrum made sense if it was simply an extremely large redshift. In other words, 3C273 was moving away from us at an incredible one-tenth the speed of light.

Recent discoveries have lead to new insight into how quasars might work. Learning more about 3c273 and other quasars helps to discover more about the history, large-scale structure, and future of our universe. Our own group of galaxies is about ten billion years old. In some cases, the photons we observe from the most distant quasars are comparable to the age of our galaxy!

Galactic Nuclei

Thanks to radio and X-ray observation, it is now apparent that the centers of galaxies like our own are home to as-of-yet unexplained energetic reactions. Some galaxies are called active galaxies, as they are further away and their nuclei emit far more radiation than galaxies like our own. Quasars are the most energetic and distant of all three objects. It is believed that the nucleus of a quasar is so bright that it hides the relatively dim surrounding galaxy. The activity in the nuclei of galaxies and active galaxies has similar characteristics to the activity taking place in quasars, and since it is easier to observe, it helps verify theories that explain how quasars work.

Black Holes

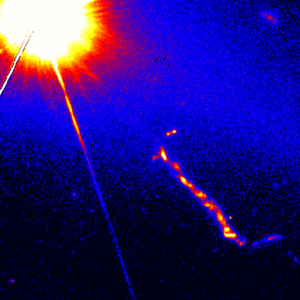

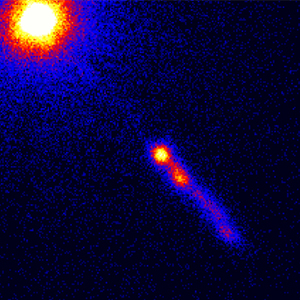

What is the engine behind the massive amounts of energy released by quasars? A clue is provided by the jet of 3C273, a radio, optical and X-ray spike that extends over a hundred thousand light years into space. This pattern points to a rotating, supermassive object. According to theory, matter from the surrounding galaxy orbits this object in what is called an accretion disk. Whenever matter from the disk is pulled by gravity into the center, the resulting electromagnetic forces could produce a beam of high-energy particles that would be observed as a jet at radio, optical and X-ray energies.

LEFT:Optical of 3C273 (Credit:NASA/STScI)

RIGHT: X-ray of 3C273 (Credit: NASA/CXC/ SAO/H. Marshall et al.)

Any object with enough mass to produce these jets of energy would certainly collapse on itself due to its own gravity. Also, both quasars and active galaxies are seen to have massive, dark objects at their core. In fact, the only object known to theory that fits these criteria is a black hole, an object so massive that not even light can escape its gravitational pull!