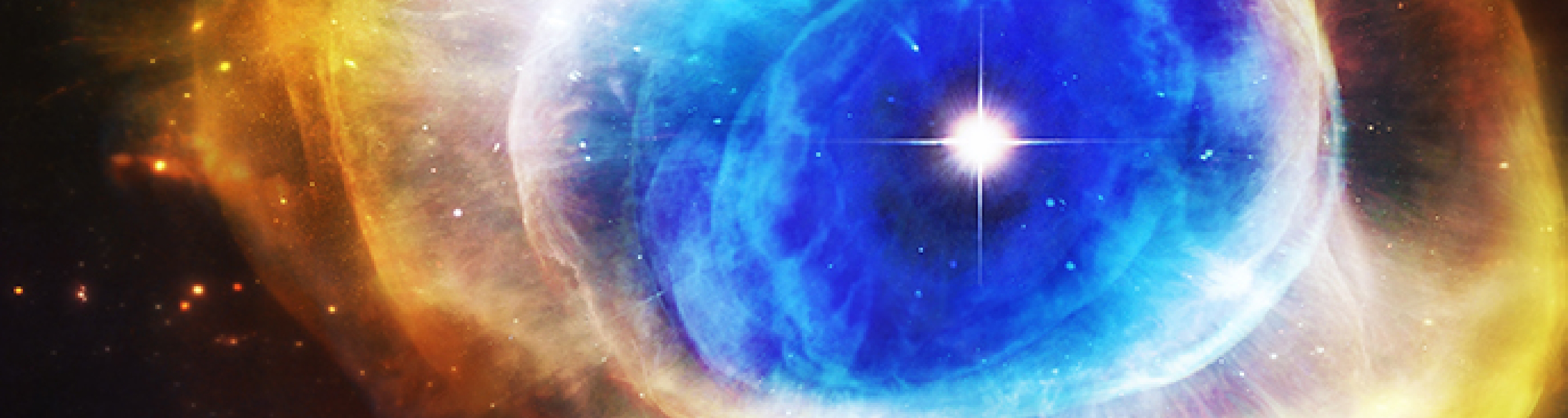

The Helix Nebula in 3D

When a star like our Sun runs out of fuel, it expands and its outer layers puff off, and then the core of the star shrinks. This phase is known as a "planetary nebula," and astronomers expect our Sun will experience this in about 5 billion years. Though they are a phase of stellar evolution, they are called “planetary nebulas” because historically, some of them resembled a planet when viewed through a small telescope.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Ultraviolet: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSC; Optical: NASA/STScI(M. Meixner)/ESA/NRAO(T.A. Rector); Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/K. Su & NASA/WISE

A Multiwavelength view of the Helix Nebula

A planetary nebula represents a phase of a star’s life. When a star like the Sun uses up all of the hydrogen in its core, it expands into a red giant, with a radius that increases by tens to hundreds of times. In this phase, a star sheds most of its outer layers, eventually leaving behind a hot core that will soon contract to form a dense white dwarf star. A fast wind emanating from the hot core rams into the ejected atmosphere, pushes it outward, and creates the graceful, shell-like filamentary structures seen with optical telescopes. These end stages of a star’s life can be utterly beautiful as is the case with this planetary nebula called the Helix Nebula. Astronomers study these objects by looking at them in all kinds of light, including X-rays that the Chandra X-ray Observatory sees:

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC; Ultraviolet: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSC; Optical: NASA/STScI(M. Meixner)/ESA/NRAO(T.A. Rector); Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/K. Su

This selection of Helix Nebula images show the same field of view across infrared data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, optical light from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, ultraviolet from NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX), and X-rays from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. The images of Helix are each about four light years across. View these images in an interactive format with NASA’s Universe of Learning.

The glow from the planetary nebula appears surprisingly similar across some of these different kinds of light, from ultraviolet to infrared. But there are key differences.

The intense ultraviolet radiation from the white dwarf heats up the expelled layers of gas, which shine brightly in the infrared. GALEX picked out the ultraviolet light pouring out of this system, shown throughout the nebula in blue, while Spitzer shows the detailed infrared signature of the dust and gas in yellow. A portion of the extended field beyond the nebula in the first image on this page was observed by NASA’s all-sky Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE).

Chandra data shows the white dwarf star that formed in the center of the nebula, a tiny white pinprick of light.

The bright magenta-purple circle in the center is the combined ultraviolet and infrared glow of a dusty disk circling the white dwarf (the disk itself is too small to be resolved). This dust was most likely kicked up by comets that survived the death of their star. Before the star died, its comets, and possibly planets, would have orbited the star in an orderly fashion. When the star ran out of hydrogen to burn, and blew off its outer layers, the icy bodies and outer planets would have been tossed about and into each other, kicking up an ongoing cosmic dust storm. Any inner planets in the system would have burned up or been swallowed as their dying star expanded.

View these images in an interactive format

Helix in 3D

Helix Nebula 3D model credit: INAF/Sal Orlando

As the planetary nebula is formed, the leftover stellar core eventually becomes a white dwarf star (see bright white spot at center). The Helix nebula, also known as NGC 7293, is located in the constellation Aquarius. It is one of the closest planetary nebulas to Earth, being less than 700 light-years away from us. This 3D model is an impression derived from data obtained with several optical filters by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.

Helix Nebula Sonification

Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), & T.A. Rector (NRAO); Sonification: SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)

This sonification (a translation of data from image into sound) depicts the optical data from the Hubble Space Telescope of the Helix Nebula. The sonification scans from left to right, where red light is assigned lower pitches and blue light is assigned higher pitches. Just as the frequencies of light increase from red to blue, frequencies of sound increase from low to high pitches.

3D Printing: Print Your Own Planetary Nebula:

This printable file was created by the Chandra team from the 3D model by Sal Orlando (INAF). The outer layers of the Sun-like star have been puffed off, and the stellar material is shown looking like a fried egg in the 3D print. The stellar core or white dwarf is too small to be visible in the 3D print but would be tucked inside at the center of the model. The structure around the edges depicts the material ejected as the star transitioned to its planetary nebula stage.

This is a simple one-part model. In our printing tests, this model did not need any support structures as the angle is gradual enough to build up onto itself.

File for 3D Printing Helix Nebula

![]()

Helix Nebula 3D model

STL

RESOURCES

DOWNLOADABLES

3D Print Your Own Helix Nebula Handout

LINKS TO OTHER ACTIVITIES

Coding & Astronomy

Recoloring the Universe with Pencil Code

3D Printing

Universe in 3D

Make the Most of Your Universe

Published: April 2024